For Canada, the War of 1812 is often viewed as a foundational “war of independence”—not from Britain, but from the United States. While the conflict was a global byproduct of the Napoleonic Wars, for the inhabitants of Upper and Lower Canada, it was a desperate struggle for survival against an invading force.

The Context: A Colony Under Threat (1812)

By June 1812, the United States declared war on Great Britain. From a Canadian perspective, the reasons (maritime rights and impressment) felt distant. The immediate reality was that the U.S. intended to annex British North America.

Thomas Jefferson famously remarked that the acquisition of Canada would be a “mere matter of marching.” At the time, Upper Canada (Ontario) was sparsely populated, largely by “Late Loyalists” whose allegiance to the Crown was suspect to the British authorities.

The Key Players

- Major-General Isaac Brock: The energetic military administrator of Upper Canada.

- Tecumseh: The Shawnee leader who formed a vital confederacy of First Nations to stop American westward expansion.

- Charles de Salaberry: A French-Canadian officer who led the defense of Lower Canada.

1812: The Year of Miracles

The war began with American attempts to cross the border at three points: the Detroit River, the Niagara River, and the route to Montreal.

- The Fall of Detroit (August): In a brilliant psychological move, Brock and Tecumseh intimidated U.S. General William Hull into surrendering Detroit without a major fight. This victory secured the support of the First Nations and galvanized the Canadian militia.

- Battle of Queenston Heights (October): This was the first major invasion attempt across the Niagara River. While the British and Mohawk warriors repelled the Americans, the victory was bittersweet: Sir Isaac Brock was killed by a sharpshooter while leading a charge.

1813: Fire and Steel

The second year was characterized by more professional American campaigning and the burning of civilian centers.

- The Burning of York (April): American forces captured York (modern-day Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada. They burned the Parliament buildings and looted the town, an act that would later justify the British burning of Washington, D.C.

- Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams (June): Two pivotal battles in the Niagara peninsula stopped American momentum. Notably, Laura Secord trekked 30 kilometers through the woods to warn British forces of a surprise American attack, leading to the victory at Beaver Dams.

- Battle of the Châteauguay (October): In Lower Canada, a force comprised almost entirely of French-Canadian “Voltigeurs” and Mohawk warriors turned back a much larger American army intent on capturing Montreal. This proved that French Canadians were committed to defending their land against American republicanism.

1814: The Bloody Stalemate

By 1814, the Napoleonic Wars in Europe were ending, allowing Britain to send veteran “Peninsular” troops to Canada.

- Lundy’s Lane (July): This was the bloodiest battle ever fought on Canadian soil. Taking place near Niagara Falls, it was a chaotic night battle that ended in a tactical draw but forced the Americans to abandon their offensive in the peninsula.

- The Burning of Washington (August): In retaliation for York, British forces (including many who had served in Canada) captured Washington and burned the White House and the Capitol.

The Aftermath and Legacy

The Treaty of Ghent (1814) returned all captured territories to their pre-war owners (status quo ante bellum). While the treaty changed no borders, the impact on Canada was profound:

| Impact Area | Result for Canada |

| National Identity | Created a shared sense of pride between English and French speakers in defending their home. |

| First Nations | The greatest losers of the war. With the death of Tecumseh (1813), the dream of an independent Indigenous buffer state vanished. |

| Security | Led to the construction of massive fortifications like the Rideau Canal (to provide a secure supply route away from the American border). |

| Politics | Reinforced a conservative, pro-British sentiment that delayed the move toward responsible government for decades. |

“The War of 1812 was the first time that the various peoples of Canada—British regulars, French-Canadian militia, and Indigenous warriors—fought together for a common cause.”

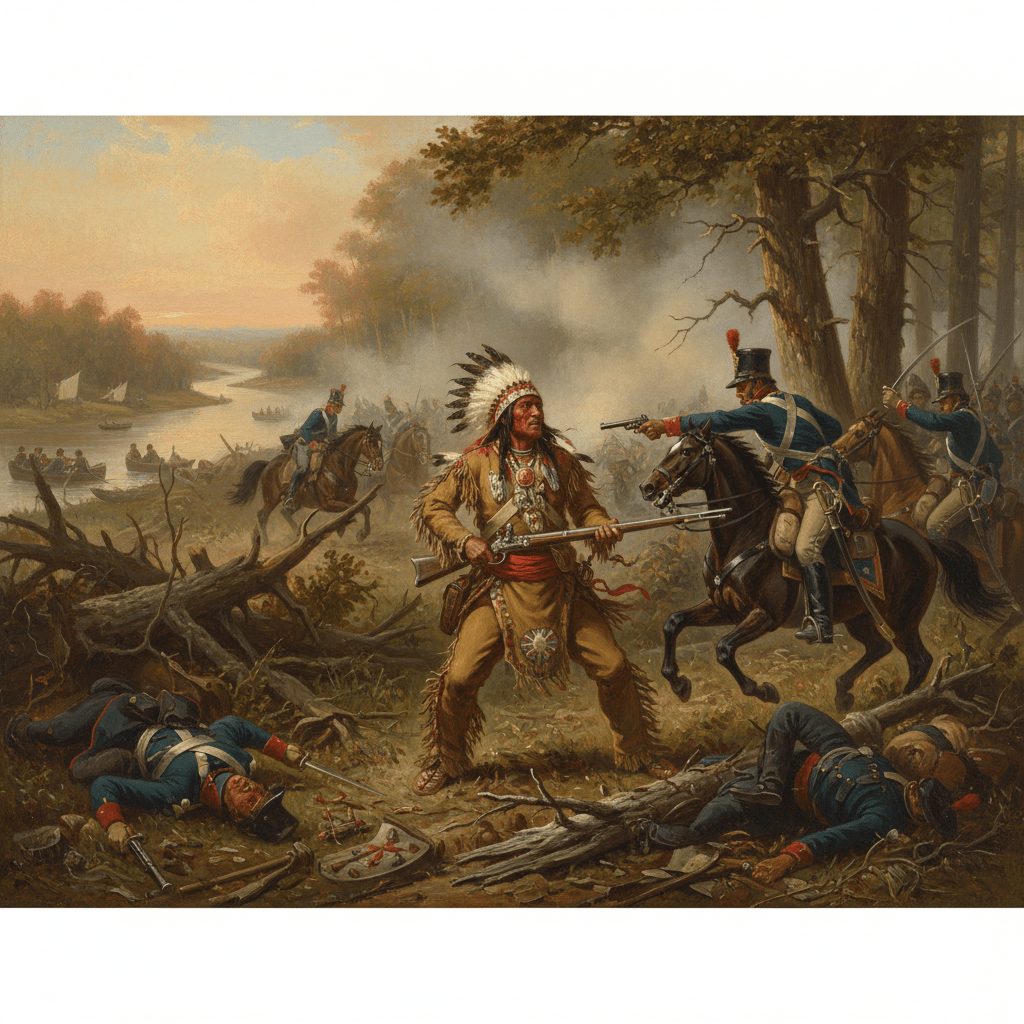

From the Canadian perspective, the War of 1812 was not just a conflict of British regulars and American invaders; it was a war where Indigenous alliances were the deciding factor in the colony’s survival.

The contributions of leaders like Tecumseh and John Norton provided the British with the specialized tactical skills—and the psychological edge—necessary to overcome massive numerical disadvantages.

Tecumseh: The Visionary and the Strategist

Tecumseh, a Shawnee war chief, did not fight for the British Empire out of loyalty to the Crown. He fought for the survival of an Independent Indigenous Confederacy that would act as a buffer state between the U.S. and British North America.

- The Psychological War at Detroit (August 1812): Tecumseh’s most famous contribution was at the Siege of Detroit. He had his warriors march in a circle through a clearing, disappearing into the woods only to reappear again. This created the illusion of a force thousands strong. Terrified of a “frontier massacre,” U.S. General Hull surrendered the fort and 2,500 soldiers to a force half that size.

- The Loss at the Thames (October 1813): After the British lost control of Lake Erie, General Procter ordered a retreat. Tecumseh was forced to make a stand at the Battle of the Thames (Moraviantown). He was killed in action, and with him died the dream of a unified Indigenous state.

John Norton (Teyoninhokarawen): The “Open Door”

John Norton was a complex figure—born in Scotland to a Cherokee father and Scottish mother, he was adopted by the Mohawk and became a war chief of the Six Nations of the Grand River.

- The Turning Tide at Queenston Heights (October 1812): After General Brock fell, the British line was in chaos. Norton led a group of only 80 Grand River Mohawk and Delaware warriors up a hidden path on the escarpment. They pinned down over 1,000 Americans with sniper fire and war cries, delaying the invasion long enough for British reinforcements to arrive. Historians often credit Norton, not the British regulars, with “saving the day” after Brock’s death.

- Tactical Scouting: Norton’s warriors acted as the “eyes and ears” of the British army. Before the Battle of Stoney Creek, his scouts provided the intelligence for the daring night raid that broke the American occupation of the Niagara Peninsula.

The “War of the Woods”

Indigenous warfare differed significantly from the European “Line and Column” style. This gave the Canadian defense a unique advantage in the dense forests of Upper Canada.

- Beaver Dams (June 1813): This battle is a textbook example of Indigenous tactical superiority. While Laura Secord provided the warning, the battle itself was fought almost entirely by 400 Kahnawake and Mohawk warriors. They ambushed an American column of 600 men in the woods, using the terrain so effectively that the Americans surrendered to a small British detachment purely out of fear of the warriors in the trees.

- The “Shadow” Factor: The mere presence of Indigenous warriors often forced American commanders to remain hunkered down in forts like Fort George, afraid to send out patrols or forage for food, effectively neutralizing their superior numbers.

Comparison of Roles

| Leader | Primary Group | Key Contribution | End of War |

| Tecumseh | Western Confederacy (Shawnee, Ojibwe, etc.) | Secured the West (Detroit); provided the “Buffer State” vision. | Killed in action at the Battle of the Thames (1813). |

| John Norton | Six Nations (Grand River Mohawk) | Decisive intervention at Queenston Heights; elite scouting. | Retired to Cherokee territory; later moved back to Upper Canada. |

| Dominique Ducharme | Kahnawake (Lower Canada Mohawk) | Led the ambush at Beaver Dams that demoralized U.S. forces. | Remained a prominent leader in Lower Canada. |

The Tragic Conclusion

While Canada “won” the war by remaining British, the Indigenous nations were the only true losers. In the Treaty of Ghent, the British failed to secure the independent buffer state they had promised Tecumseh. The border remained exactly where it was, and the path was cleared for the American “Manifest Destiny” to push westward, largely unchecked.

Would you like to explore the specific battle maps of Queenston Heights or Beaver Dams to see how these tactical maneuvers were executed?

Analyzing the tactical maps of these two battles reveals why Indigenous involvement was the “X-factor” that the American military simply couldn’t account for.

The Battle of Queenston Heights (October 13, 1812)

While history often focuses on General Brock’s charge, the tactical map shows that it was the Indigenous flanking maneuver that actually won the day.

- The Problem: The Americans had captured a “redan” (a clifftop gun battery) and held the high ground. A frontal assault by British regulars was suicidal (as Brock’s death proved).

- The Indigenous Maneuver: John Norton and about 80 Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) warriors did not follow the British path. Instead, they climbed a hidden, unguarded track further west along the escarpment.

- The “Pin”: Once on top, they used the heavy woods to “pin” the Americans. By firing from cover and moving constantly, they created the impression of a much larger force. This pinned the 1,000+ Americans to the cliff’s edge, preventing them from organizing a defense until British reinforcements under General Sheaffe arrived to finish the flanking movement.

The Battle of Beaver Dams (June 24, 1813)

This is widely considered a “textbook” Indigenous victory. The battle took place in the dense “Beechwoods” (near modern-day Thorold, ON).

- The Ambush Setup: After Laura Secord provided the warning, 300 Kahnawake and 100 Mohawk warriors positioned themselves in a “U-shaped” ambush along a narrow forest trail.

- The “War of the Woods”: As the American column of 600 men entered the woods, the warriors attacked from the flanks and rear. The Americans, trained for open-field combat, were helpless. They tried to retreat into an open clearing to use their cannons, but the warriors remained in the tree line, picking them off.

- The Bluff: After three hours of psychological terror, British Lieutenant FitzGibbon arrived with only 50 regulars. He walked into the American camp with a white flag and told the commander, Colonel Boerstler, that he was surrounded by thousands of “savage” warriors he could no longer control. Terrified of a massacre, the Americans surrendered their entire force to a group they actually outnumbered.

Visualizing the Impact

| Battle | British Regular Strategy | Indigenous Tactical Contribution |

| Queenston Heights | Frontal Uphill Charge (Failed) | Secret Ascent & Flanking Suppression (Succeeded) |

| Beaver Dams | Negotiation / Formal Surrender | 3-Hour Guerilla Ambush & Total Demoralization |

Places to Visit Today

If you are interested in walking these grounds, several key sites preserve these specific tactical locations:

- Landscape of Nations Memorial (Queenston Heights): A dedicated site honoring the Indigenous contribution specifically at that battle.

- Battle of Beaverdams Park (Thorold): Features monuments and plaques marking the site of the ambush and surrender.

- DeCew House Heritage Park: The ruins of the stone house where Norton and FitzGibbon were stationed when Laura Secord arrived.